Diagnostisch proces

Aanmelding en verwijzing

Bij patiënten met osteoporose of met osteoporose samenhangende klachten onderzoekt de fysiotherapeut welk(e) probleemgebied(en) (immobiliteit, pijn, een verhoogd valrisico en/of status na een fractuur) op de voorgrond staat/staan. Uitgangspunt is de hulpvraag van de patiënt.

Indien een patiënt is verwezen door de huisarts of een medisch specialist moeten op de verwijzing de volgende gegevens vermeld staan: naam patiënt (eventueel adres en gegevens over de zorgverzekering); het burgerservicenummer (BSN); de datum van de verwijzing; de diagnose (eventueel diagnosecode); de verwijsindicatie; de hulpvraag van de patiënt; relevante gegevens over de gezondheidstoestand van de patiënt (medicatie en relevante medische en psychosociale gegevens, zoals leefstijl); naam van de verwijzer; handtekening van de verwijzer; naam van de huisarts (indien deze niet de verwijzer is).

Patiënten kunnen zich ook op eigen initiatief melden bij de fysiotherapeut of via een verwijzing door huisarts of medisch specialist, de Directe Toegankelijkheid Fysiotherapie (DTF).

B.2 Directe Toegankelijkheid Fysiotherapie (DTF)

Met ingang van 1 januari 2006 is directe toegankelijkheid van de fysiotherapeut wettelijk mogelijk. In overleg met en met toestemming van de patiënt wordt in verwijzende en terugverwijzende zin samengewerkt met andere behandelaars. Indien noodzakelijke medische gegevens ontbreken, moet de fysiotherapeut contact opnemen met de huisarts of medisch specialist. Indien een patiënt zich zonder verwijzing aanmeldt, voert de fysiotherapeut, na inventarisatie van de hulpvraag, een screeningsproces uit. In geval van verdenking door de fysiotherapeut op een ander probleem dan dat waarvoor de patiënt zich bij de fysiotherapeut meldde, is (terug)verwijzing naar de huisarts van belang in verband met het instellen van medicatie en/of het uitsluiten van onbegrepen klachten.

Het screeningsproces is aan het methodisch handelen toegevoegd in het kader van de DTF en is bedoeld om na te gaan of fysiotherapeutische behandeling is geïndiceerd. De screening bestaat uit: aanmelding, inventarisatie van de hulpvraag, screening op ’pluis/niet-pluis’ en informeren en adviseren naar aanleiding van de bevindingen van het screeningsproces. De fysiotherapeut stelt binnen een beperkte tijd gericht vragen, en neemt tests af op grond van de diagnostische bevindingen, en stelt vast of er al dan niet sprake is van een binnen het competentiegebied van de individuele fysiotherapeut vallend patroon van tekens en symptomen. Belangrijk aspect van de screening op pluis/niet-pluis is identificatie van eventuele rode vlaggen. De fysiotherapeut moet zich een beeld vormen van de klachten en symptomen en de eventuele aanwezigheid van zogeheten gele en rode vlaggen. Gele vlaggen zijn aanwijzingen voor psychosociale en gedragsmatige risicofactoren voor het onderhouden en/of verergeren van de gezondheidsproblemen.

Screening is niet noodzakelijk indien er sprake is van een verwijzing. Wel moet de therapeut gedurende het diagnostisch en therapeutisch proces alert blijven op signalen en symptomen waarvoor eventueel contact met een arts nodig is.

De werkgroep formuleerde de volgende aanbeveling:

(1) Rode vlaggen

Bij elke patiënt dient de fysiotherapeut na te gaan of er rode vlaggen aanwezig zijn. In geval van een of meerdere rode vlaggen moet de patiënt worden geïnformeerd en krijgt de patiënt het advies om contact op te nemen met de huisarts (in geval van Directe Toegankelijkheid Fysiotherapie, DTF) of verwijzend arts.

Als iemand met de diagnose osteoporose zich bij de fysiotherapeut aanmeldt zonder verwijzing (DTF), zal eerst een screening plaatsvinden. Deze is bedoeld om na te gaan of fysiotherapeutische behandeling is geïndiceerd. Hiertoe moet de fysiotherapeut zich een beeld vormen van de klachten en symptomen en de eventuele aanwezigheid van zogeheten rode en gele vlaggen. Rode vlaggen zijn patronen van symptomen of tekenen (waarschuwingssignalen) die kunnen wijzen op min of meer ernstige pathologie, die aanvullende medische diagnostiek vereisen. Herkenning van het klachtenpatroon dat specifiek is voor osteoporose is van belang om vast te kunnen stellen of er rode vlaggen aanwezig zijn die niet bij dit patroon passen. Hierna staan de rode vlaggen vermeld voor osteoporose, zoals verzameld op basis van de literatuur en expert opinion.

Algemene rode vlaggen

- pijn die niet te provoceren of te reduceren is door houdingen en/of bewegingen

- zich uitbreidende en toenemende pijn

- koorts

- (nachtelijk) transpireren

- misselijkheid

- braken

- diarree

- (onnatuurlijke) bleekheid

- duizeligheid/ flauwvallen

- ongewenst gewichtsverlies (> 5 kg per maand)

- acuut ontstaan van klachten zonder verklaring

- eetlustdaling

- langdurig gebruik van corticosteroïden

- onbegrepen tekenen of symptomen na recent trauma

- duidelijke symptomen of tekenen van ernstige weerstandsdaling, zoals schimmelinfecties, onbegrepen ontstekingsbeelden

- in combinatie met progressieve algehele zwakte

- evidente verlamming

- evidente gevoelsstoornis

- leeftijd (> 50 jaar) in combinatie met pathologie

- nachtelijke pijn

- bekend met maligniteiten

- maligniteit in de familieanamnese

- psychopathologie/psychiatrie

Specifieke rode vlaggen

- onverklaarbare pijn

- zwelling in de lies (maligniteit?)

- (hevige) pijn in rust en zwelling (zonder trauma) (maligniteit?)

In geval van een of meerdere rode vlaggen moet de fysiotherapeut de patiënt hierover informeren. Ook de huisarts moet, in overleg met de patiënt, over de rode vlaggen worden geïnformeerd. Daarnaast krijgt de patiënt het advies om contact op te nemen met de huisarts of behandelend specialist. Over de communicatie tussen de fysiotherapeut en de huisarts zijn lokaal afgestemde afspraken mogelijk ten aanzien van de gang van zaken als de fysiotherapeut rode vlaggen constateert.

Bij onduidelijkheid over de diagnose krijgt de patiënt het advies om contact op te nemen met de huisarts. Deze kan verder onderzoek verrichten.

Tijdens deze screeningsfase kunnen zich 5 mogelijke situaties voordoen (volgens de KNGF-nascholingsmodule DTF):

- De gepresenteerde symptomen passen volledig in een voor de fysiotherapeut bekend patroon van klachten als gevolg van osteoporose.

Actie: overleg met de patiënt en besluit of verder fysiotherapeutisch onderzoek geïndiceerd is. - De gepresenteerde symptomen passen niet in een voor de fysiotherapeut bekend patroon van klachten als gevolg van osteoporose.

Actie: informeer de patiënt en, in overleg met de patiënt, ook de huisarts en adviseer de patiënt om contact op te nemen met de huisarts. - De aanwezige symptomen passen in een voor de fysiotherapeut bekend patroon van klachten als gevolg van de osteoporose, maar er wijken een of meerdere bijkomende symptomen af van het patroon.

Actie: informeer de patiënt en, in overleg met de patiënt, ook de huisarts en adviseer de patiënt om contact op te nemen met de huisarts. - De gepresenteerde symptomen passen in een voor de fysiotherapeut bekend patroon van klachten als gevolg osteoporose. Het beloop is echter afwijkend.

Actie: informeer de patiënt en, in overleg met de patiënt, ook de huisarts en adviseer de patiënt om contact op te nemen met de huisarts. - Er zijn een of meerdere rode vlaggen aanwezig.

Actie: informeer de patiënt en in overleg met de patiënt ook de huisarts en adviseer de patiënt om contact op te nemen met de huisarts.

Op basis van bovenstaande formuleerde de werkgroep de volgende aanbeveling:

1 Rode vlaggen

Bij elke patiënt dient de fysiotherapeut na te gaan of er rode vlaggen aanwezig zijn. In geval van een of meerdere rode vlaggen moet de patiënt worden geïnformeerd en krijgt de patiënt het advies om contact op te nemen met de huisarts (in geval van Directe Toegankelijkheid Fysiotherapie, DTF) of verwijzend arts (niveau 4).

Kwaliteit van de gevonden artikelen: D.

B.2.1 Inventarisatie hulpvraag

Bij de inventarisatie van de hulpvraag is het van belang de belangrijkste klachten, het beloop daarvan en de doelstellingen van de patiënt te achterhalen.

B.2.2 Screening pluis/niet-pluis

Op basis van leeftijd, geslacht, incidentie en prevalentie en de gegevens over ontstaanswijze, symptomen en verschijnselen moet de fysiotherapeut kunnen inschatten of symptomen en verschijnselen pluis of niet-pluis zijn, om te kunnen besluiten of verder fysiotherapeutisch onderzoek geïndiceerd is. De fysiotherapeut is alert op onbekende patronen, bekende patonen met één of meer afwijkende symptomen dan wel een afwijkend / ongunstig beloop, en op rode vlaggen.

Bij iedere patiënt die zich zonder verwijzing (DTF) aanmeldt bij de fysiotherapeut, zal eerst een screening plaatsvinden. Deze screening is bedoeld om na te gaan of fysiotherapeutische behandeling is geïndiceerd.

Rode vlaggen zijn patronen van symptomen of tekenen (waarschuwingssignalen) die kunnen wijzen op min of meer ernstige pathologie, die aanvullende medische diagnostiek vereisen. Herkenning van het klachtenpatroon dat specifiek is voor osteoporose is van belang teneinde vast te kunnen stellen of er specifieke rode vlaggen aanwezig zijn die niet bij dit patroon passen.

B.2.3 Informeren en adviseren

Aan het einde van het screeningsproces wordt de patiënt geïnformeerd over de bevindingen. Indien het patroon onbekend is, een of meerdere symptomen afwijken van een voor de individuele fysiotherapeut bekend patroon, het patroon een afwijkend / ongunstig beloop heeft of bij aanwezigheid van rode vlaggen (conclusie: niet-pluis), wordt de patiënt geadviseerd om contact op te nemen met de huisarts.

Indien geen afwijkende bevindingen worden vastgesteld, wordt de patiënt geïnformeerd over de mogelijkheid om door te gaan met het diagnostisch proces.

B.3 Anamnese

Als bij osteoporose pijn op de voorgrond staat, richt de intake zich in eerste instantie op stoornissen in functies en anatomische eigenschappen. In alle gevallen richt de intake zich op de beperkingen in activiteiten en participatie en de invloed van persoonlijke en omgevingsfactoren.

Aandachtspunten in de anamnese

- inventarisatie van de hulpvraag

- inventarisatie van de verwachtingen;

- ontstaanswijze en aard van de symptomen.

- inventarisatie van de klachten:

- de ernst van de stoornissen en het soort stoornissen, beperkingen en participatieproblemen;

- nevenklachten, zoals (chronische) gewrichtsklachten, ademhalingsklachten, obstipatie; klachten bij bukken en opkomen, acute of chronische rugpijn;

- factoren die verband houden met het ontstaan en het beloop van de klachten;

- leefstijl en veranderbereidheid;

- eerdere diagnostiek, behandeling en resultaat hiervan.

- inventarisatie van de status praesens:

- stoornissen, beperkingen, participatieproblemen samenhangend met osteoporose;

- nevenpathologie;

- huidig medicijngebruik/nevenbehandeling(en);

- aantal keren gevallen (en zo ja hoe) in het afgelopen jaar;

- huidige activiteiten- en participatieniveau;

- activiteiten die de patiënt belangrijk vindt en graag wil blijven doen / hervatten.

- inventarisatie van het risico op fracturen:

- verhoogd risico op osteoporose;

- functiestoornissen van spieren, gewrichten en stoornissen in gang en balans (zie paragraaf B.4.2).

Met de FRAX Calculation Tool kan het risico op fracturen worden berekend aan de hand van risicofactoren voor osteoporose. De FRAX is ontwikkeld door de WHO. Ga naar de FRAX.

In de FRAX wordt geen rekening gehouden met ‘vallen’ als risicofactor, wat bij patiënten die regelmatig vallen kan leiden tot een onderschatting van het fractuurrisico. De Garvan Fracture Risk Calculator houdt wel rekening met ‘vallen’ als risicofactor.

Aan de hand van de volgende checklist kunnen risicofactoren voor fracturen en vallen worden geïnventariseerd.

Checklist risicofactoren voor vallen en fracturen

Verhoogd risico op fracturen

- leeftijd > 55 jaar;

- een fractuur na het 50e levensjaar (of aanwezig wervelfractuur);

- familie: moeder heupfractuur;

- laag lichaamsgewicht (< 67 kg);

- gebruik corticosteroïden (> 7,5 mg/dag);

- visusstoornissen;

- ernstige immobilisatie.

Verhoogd valrisico

- medicijngebruik: antidepressiva, sedativa, enzovoort;

- cognitieve stoornissen (score op de Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) < 24)

Bij mensen met een verhoogd risico op osteoporose zal een risicoscreening op factoren voor osteoporose en vallen worden uitgevoerd.

De werkgroep formuleerde de volgende aanbeveling:

1 Rode vlaggen

Bij elke patiënt dient de fysiotherapeut na te gaan of er rode vlaggen aanwezig zijn. In geval van een of meerdere rode vlaggen moet de patiënt worden geïnformeerd en krijgt de patiënt het advies om contact op te nemen met de huisarts (in geval van Directe Toegankelijkheid Fysiotherapie, DTF) of verwijzend arts (niveau 4).

Kwaliteit van de gevonden artikelen: D.

De werkgroep formuleerde de volgende aanbeveling:

2 Anamnese

Bij het inventariseren van de gezondheidsproblemen van mensen met osteoporose moet de fysiotherapeut de gezondheidstoestand in kaart brengen door, volgens het ICF-model, gebruik te maken van de gezondheidsdomeinen: functies en anatomische eigenschappen, activiteiten, participatie, externe en persoonlijke factoren.

De anamnese heeft tot doel duidelijkheid te verkrijgen over de klacht en de aandoening. Hierbij gaat het bijvoorbeeld om aard, oorzaak en ontstaanswijze, lokalisatie, ernst en beloop van de klacht en aandoening en mogelijke psychosociale en gedragsmatige risicofactoren voor het onderhouden en/of verergeren van de gezondheidsproblemen (gele vlaggen). De fysiotherapeut inventariseert de risicofactoren voor een lage BMD en een hoog valrisico heeft (paragraaf A.4) en gaat na of de patiënt een verhoogd risico heeft op fracturen.

Cognitieve stoornissen zijn geassocieerd met een verhoogd valrisico. Om cognitieve stoornissen te inventariseren, kan de fysiotherapeut gebruikmaken van de Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE). De MMSE is een betrouwbaar, valide en bruikbaar meetinstrument voor het opsporen van cognitieve stoornissen bij ouderen.94,95 De vragenlijst bestaat uit 2 delen. Het eerste deel betreft oriëntatie, geheugen en aandacht. Het tweede deel test de mogelijkheid van personen om verbale en geschreven commando’s te benoemen, te volgen en/of te kopiëren. De maximale totale score is 30. Een score lager dan 24 is grofweg indicatief voor cognitieve stoornissen.96 Deze score wordt geassocieerd met een hoger valrisico.97

Bij patiënten met osteoporose of met osteoporose samenhangende klachten onderzoekt de fysiotherapeut welk(e) probleemgebied(en) (immobiliteit, een verhoogd valrisico en/of status na een fractuur) op de voorgrond staat/staan. De hulpvraag van de patiënt is het uitgangspunt.

Gele vlaggen zijn aanwijzingen voor psychosociale en gedragsmatige risicofactoren voor het onderhouden en/of verergeren van de gezondheidsproblemen.

Gele vlaggen

Ideeën omtrent de pijn

- De patiënt denkt dat de pijn beschadigend werkt.

- De patiënt denkt dat de pijn oncontroleerbaar is.

- De patiënt denkt dat rust het beste is en dat activiteiten de pijn verergeren.

Gedrag

- De patiënt gebruikt hulpmiddelen, medicatie en pijnstillers.

- De patiënt ligt veel op bed en vermijdt dagelijkse activiteiten.

- De patiënt slaapt slechter sinds het ontstaan van de pijn.

Financiële consequenties

- De patiënt heeft er geen financieel belang bij om het werk te hervatten.

- Er was sprake van uitkeringsproblematiek bij eerder verzuim van het werk gedurende een langere periode (bijvoorbeeld 12 weken), die was gerelateerd aan pijn.

Diagnostiek en behandeling

- Er bestaat verwarring omtrent de diagnose.

- De patiënt is afhankelijk van eerdere behandelingen.

- Er is sprake van passieve behandelmodaliteiten.

- De patiënt onderging in het verleden een reeks ineffectieve behandelingen.

Emoties

- De patiënt is bang om het werk te hervatten.

- De patiënt is depressief en sneller geïrriteerd dan voorheen.

- De patiënt is angstig en heeft een toegenomen aandacht voor lichamelijke gewaarwordingen (inclusief verhoogde arousal).

Gezin

- De patiënt heeft een overbeschermende partner die het gevaar op beschadiging en letsel benadrukt.

- De patiënt krijgt onvoldoende steun bij de hervatting van de activiteiten.

Bepaalde beroepen

- De patiënt is verpleegkundige, vrachtwagenchauffeur of bouwvakker, of zwaar tillen hoort bij zijn beroep.

- De patiënt is ervan overtuigd dat werk schadelijk is.

- De patiënt heeft problemen in de huidige werksetting.

- De patiënt heeft negatieve eerdere ervaringen bij werkhervatting na een episode van pijn.

Op basis van bovenstaande formuleerde de werkgroep de volgende aanbeveling:

2 Anamnese

Bij het inventariseren van de gezondheidsproblemen van mensen met osteoporose moet de fysiotherapeut de gezondheidstoestand in kaart brengen door, volgens het ICF-model, gebruik te maken van de gezondheidsdomeinen: functies en anatomische eigenschappen, activiteiten, participatie, externe en persoonlijke factoren (niveau 4).

Kwaliteit van de gevonden artikelen: D.

1. Elders PJM, Leusink GL, Graafmans WC, Bolhuis AP, Spoel OP van der, Keimpema JC, et al. NHG-standaard Osteoporose. Huisarts Wet. 2005;48(11)(559):570.

2. Conceptrichtlijn Osteoporose en fractuurpreventie derde herziening. Utrecht: Kwaliteitsinstituut voor de Gezondheidszorg CBO; 2010.

3. Hendriks HJM, Bekkering GE, Ettekoven H van, Brandsma JW, Wees PhJ van der, Bie RA de. Development and implementation of national practice guidelines: A prospect for quality improvement in physiotherapy. Introduction to the method of guideline development. Physiother. 2000;86:535-47.

4. Hendriks HJM, Ettekoven H van, Wees PhJ van der. Eindverslag van het project Centrale richtlijnen in de fysiotherapie (Deel 1). Achtergronden en evaluatie van het project. Amersfoort: KNGF/NPI/CBO; 1998.

5. Hendriks HJM, Ettekoven H van, Reitsma E, Verhoeven ALJ, Wees PhJ van der. Methode voor centrale richtlijnenontwikkeling en implementatie in de fysiotherapie. Amersfoort: KNGF/NPI/CBO; 1998.

6. Hendriks HJM, Reitsma E, Ettekoven H van. Centrale richtlijnen in de fysiotherapie. Ned Tijdschr Fysiother. 1996;106:2-11.

7. van der Wees PhJ, Hendriks HJM, Heldoorn M, Custers JWH, Bie RA de. Methode voor ontwikkeling, implementatie en bijstelling van KNGF-richtlijnen. Amersfoort/Maastricht: Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie; 2007.

8. Hendriks HJM, Ettekoven H van, Bekkering T, Verhoeven A. Implementatie van KNGF-richtlijnen. Fysiopraxis. 2000;9:9-13.

9. Smits-Engelsman BCM, Bekkering GE, Hendriks HJM. KNGF-richtlijn Osteoporose. Amersfoort: Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie; 2001.

10. Jongert MWA, Overbeek K van, Chorus AMJ, Hopman-Rock M. KNGF-Beweegprogramma voor mensen met Osteoporose. Amersfoort: Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie; 2007.

11. Smits-Engelsman BCM, Kam D de, Jongert MWA. KNGF-Standaard Beweeginterventie osteoporose. Amersfoort: Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie; 2009.

12. Conference report. Consensus development conference: diagnosis, prophylaxis and treatment of osteoporosis. Am J Med. 1993;94:646-50.

13. Kanis JA. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: synopsis of a WHO report. WHO Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 1994 Nov;4(6):368-81.

14. Royal College of Physicians. Osteoporosis. Clinical guidelines for prevention and treatment. London: Royal College of Physicians; 1999.

15. Josse R, Tenenhouse AM, Adachi JD, members of the scientific advisory board. Osteoporosis Society of Canada: clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis. Can Med Ass J. 1996;155:1113-33.

16. Consensus statement. The prevention and management of osteoporosis. Med J Aust. 1997;167:S4-S15.

17. Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Physiotherapy guidelines for the management of osteoporose. London: Chartered Society of Physiotherapy; 1999.

18. Gezondheidsraad: commissie osteoporose. Preventie van aan osteoporose gerelateerde fracturen. 1998/05 Rijswijk: Gezondheidsraad; 1998.

19. Poos MJJC, Gommer AM. Osteoporose. Omvang van het probleem. Hoe vaak komt osteoporose voor en hoeveel mensen sterven eraan? Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning, Nationaal Kompas Volksgezondheid Bilthoven: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu; 2009.

20. Poos MJJC, Gommer AM. Osteoporose. Omvang van het probleem. Neemt het aantal mensen met osteoporose toe of af? Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning, Nationaal Kompas Volksgezondheid Bilthoven: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu; 2009.

21. Pols HAP, et al. CBO richtlijn Osteoporose, tweede herziene uitgave. Alphen aan den Rijn. Utrecht: kwaliteitsinstituut voor de gezondheidszorg CBO; 2002.

22. Jarvinen TL, Sievanen H, Khan KM, Heinonen A, Kannus P. Shifting the focus in fracture prevention from osteoporosis to falls. BMJ. 2008 Jan. 19;336(7636):124-6.

23. Hoeymans N, Melse JL, Schoemaker CG. Gezondheid en determinanten. Deelrapport van de Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning. 2010 Van gezond naar beter. Bilthoven: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu; 2010.

24. Lanting LC, Stam C, Hertog PC den, Burgmans MJP. Heupfractuur, omvang van het probleem, hoe vaak komen heupfracturen voor en hoeveel mensen sterven eraan? Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning, Nationaal Kompas Volksgezondheid Bilthoven: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu; 2010.

25. Melton LJ, III. Epidemiology of spinal osteoporosis. Spine. 1997 Dec 15;22(24 Suppl):2S-11S.

26. Poos MJJC, Smit JM, Groen J, Kommer GJ, Slobbe LCJ. Kosten van ziekten in Nederland. 2005: zorg voor euro’s-8. Bilthoven: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu; 2008.

27. Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet. 1996 Dec 7;348(9041):1535-41.

28. Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ, III. Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota. 1985-1989. J Bone Miner Res. 1992 Feb;7(2):221-7.

29. Bornor JA, Dilworth BB, Sullivan KM. Exercise and osteoporosis: a critique of the literature. Physiother Can. 1988;40:146-55.

30. Culham EG, Jimenez HA, King CE. Thoracic kyphosis, rib mobility, and lung volumes in normal women and women with osteoporosis. Spine. 1994 Jun 1;19(11):1250-5.

31. Gezondheidsraad: commissie osteoporose. Preventie van osteoporose. 91/21. Den Haag: Gezondheidsraad; 1991.

32. Lynn SG, Sinaki M, Westerlind KC. Balance characteristics of persons with osteoporosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997 Mar;78(3):273-7.

33. Burger H, Daele PL Van, Grashuis K, Hofman A, Grobbee DE, Schutte HE, et al. Vertebral deformities and functional impairment in men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 1997 Jan;12(1):152-7.

34. Ettinger B, Black DM, Nevitt MC, Rundle AC, Cauley JA, Cummings SR, et al. Contribution of vertebral deformities to chronic back pain and disability. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res. 1992 Apr;7(4):449-56.

35. Lyles KW, Gold DT, Shipp KM, Pieper CF, Martinez S, Mulhausen PL. Association of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures with impaired functional status. Am J Med. 1993 Jun;94(6):595-601.

36. Keene GS, Parker MJ, Pryor GA. Mortality and morbidity after hip fractures. BMJ. 1993 Nov 13;307(6914):1248-50.

37. Roche JJ, Wenn RT, Sahota O, Moran CG. Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005 Dec 10;331(7529):1374.

38. Gold DT. The clinical impact of vertebral fractures: quality of life in women with osteoporosis. Bone. 1996 Mar;18(3 Suppl):185S-9S.

39. Morree JJ de. Dynamiek van het menselijk bindweefsel. 5e druk. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum; 2008.

40. Fukada E, Yasuda I. On the piezoelectric effect of bone. J Phys Soc Japan. 1957;12:1158-62.

41. Noris-Shurez K. Elctrochemical influence of collagen piezoelectic effect in bone healing. Materials science forum. 2007;544:981-4.

42. Klein-Nulend J, Bacabac RG, Mullender MG. Mechanobiology of bone tissue. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2005 Dec;53(10):576-80.

43. Mullender M, El Haj AJ, Yang Y, Duin MA van, Burger EH, Klein-Nulend J. Mechanotransduction of bone cells in vitro: mechanobiology of bone tissue. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2004 Jan;42(1):14-21.

44. Sterck JG, Klein-Nulend J, Lips P, Burger EH. Response of normal and osteoporotic human bone cells to mechanical stress in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1998 Jun;274(6 Pt 1):E1113-E1120.

45. Burger EH, Klein-Nulend J. Mechanotransduction in bone-role of the lacuno-canalicular network. FASEB J. 1999;13 Suppl:S101-S112.

46. Mullender MG, Tan SD, Vico L, Alexandre C, Klein-Nulend J. Differences in osteocyte density and bone histomorphometry between men and women and between healthy and osteoporotic subjects. Calcif Tissue Int. 2005 Nov;77(5):291-6.

47. Fleish H. Pathophysiology of osteoporosis. Bone and Miner. 1993;22:S3-6.

48. Riggs BL, Melton LJ, III. The prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 1992 Aug 27;327(9):620-7.

49. Fitzsimmons A, Freundlich B, Bonner F. Osteoporosis and rehabilitation. Crit Rev Phys Rehabil Med. 1997;9:331-53.

50. van Helden S, Geel AC van, Geusens PP, Kessels A, Nieuwenhuijzen Kruseman AC, Brink PR. Bone and fall-related fracture risks in women and men with a recent clinical fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008 Feb;90(2):241-8.

51. Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Johansson H, De Laet C, Delmas P, et al. Predictive value of BMD for hip and other fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2005 Jul;20(7):1185-94.

52. Hui SL, Slemenda CW, Johnston CC, Jr. Baseline measurement of bone mass predicts fracture in white women. Ann Intern Med. 1989 Sep 1;111(5):355-61.

53. Nevitt MC, Johnell O, Black DM, Ensrud K, Genant HK, Cummings SR. Bone mineral density predicts non-spine fractures in very elderly women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Osteoporos Int. 1994 Nov;4(6):325-31.

54. Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, Stone K, Fox KM, Ensrud KE, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1995 Mar 23;332(12):767-73.

55. Ross PD, Davis JW, Epstein RS, Wasnich RD. Pre-existing fractures and bone mass predict vertebral fracture incidence in women. Ann Intern Med. 1991 Jun 1;114(11):919-23.

56. Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Stone KL, Palermo L, Black DM, Bauer DC, et al. Risk factors for a first-incident radiographic vertebral fracture in women > or = 65 years of age: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2005 Jan;20(1):131-40.

57. Nguyen T, Sambrook P, Kelly P, Jones G, Lord S, Freund J, et al. Prediction of osteoporotic fractures by postural instability and bone density. BMJ. 1993 Oct 30;307(6912):1111-5.

58. Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC, Lamb SE, Cumming RG, Rowe BH. Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD000340.

59. Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Kidd S, Black D. Risk factors for recurrent nonsyncopal falls. A prospective study. JAMA. 1989 May 12;261(18):2663-8.

60. Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988 Dec 29;319(26):1701-7.

61. Lajoie Y, Gallagher SP. Predicting falls within the elderly community: comparison of postural sway, reaction time, the Berg balance scale and the Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale for comparing fallers and non-fallers. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2004 Jan;38(1):11-26.

62. Morris R, Harwood RH, Baker R, Sahota O, Armstrong S, Masud T. A comparison of different balance tests in the prediction of falls in older women with vertebral fractures: a cohort study. Age Ageing. 2007 Jan;36(1):78-83.

63. Stel VS, Smit JH, Pluijm SM, Lips P. Balance and mobility performance as treatable risk factors for recurrent falling in older persons. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003 Jul;56(7):659-68.

64. Stalenhoef PA, Crebolder HFJM, Knotterus JA, Horst FGEM van der. Incidence, risk factors and consequences of falls among elderly subjects living in the community: a criteria-based analysis. Eur J Publ Health. 1997;7:328-34.

65. Oliver D, Britton M, Seed P, Martin FC, Hopper AH. Development and evaluation of evidence based risk assessment tool (STRATIFY) to predict which elderly inpatients will fall: case-control and cohort studies. BMJ. 1997 Oct 25;315(7115):1049-53.

66. Stalenhoef PA, Fiolet JFBM, Crebolder HFJM. Vallen van ouderen: een valkuil? Huisarts Wet. 1997;40:158-61.

67. Meldrum D, Finn AM. An investigation of balance function in elderly subjects who have and have not fallen. Physiother. 1993;79:839-42.

68. Stalenhoef PA, Diederiks JPM, Knotterus JA, Kester A, Crebolder HFJM. Predictors of falls in community-dwelling elderly: a prospective cohort study. In: Stalenhoef PA, editors, Falls in the elderly A primary care-based study. Maastricht: Universiteit Maastricht; 1999.

69. Graafmans WC, Ooms ME, Hofstee HM, Bezemer PD, Bouter LM, Lips P. Falls in the elderly: a prospective study of risk factors and risk profiles. Am J Epidemiol. 1996 Jun 1;143(11):1129-36.

70. Simpson JM. Elderly people at risk of falling: the role of muscle weakness. Physiother. 1993;79:831-5.

71. Paganini-Hill A, Chao A, Ross RK, Henderson BE. Exercise and other factors in the prevention of hip fracture: the leisure world study. Epidemiology. 1991;2:16-25.

72. Tromp AM, Smit JH, Deeg DJH, Bouter LM, Lips P. Predictors for falls and fractures in the longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:1932-9.

73. Wickham CAC, Walsh K, Cooper C, Barker DJP, Margretts BM, Morris J, et al. Dietary calcium, physical activity, and risk of hip fracture: a prospective study. BMJ. 1989;299:889-92.

74. Jaglal SB, Kreiger N, Darlington G. Past and present physical activity and risk of hip fracture. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:107-18.

75. Coupland C, Wood D, Cooper C. Physical inactivity is an independent risk factor for hip fracture in the elderly. J Epidemiol Comm Health. 1993;47:441-3.

76. Myers AH, Young Y, Langlois JA. Prevention of falls in the elderly. Bone. 1996 Jan;18(1 Suppl):87S-101S.

77. Carter SE, Campbell EM, Sanson-Fisher RW, Redman S, Gillespie WJ. Environmental hazards in the homes of older people. Age Ageing. 1997 May;26(3):195-202.

78. Gezondheidsraad. Voedingsnormen: calcium, vitamine D, thiamine, riboflavine, niacine, pantotheenzuur en biotine. Den Haag: Gezondheidsraad publicatie nr. 2000/12; 2000.

79. Gezondheidsraad. Naar een toereikende inname van vitamine D. Den Haag: Gezondheidsraad publicatie nr. 2008/15; 2008.

80. Mosekilde L, Viidik A. Age-related changes in bone mass, structure and strength – pathogenesis and prevention. Int J Sports Med. 1989;10:S90-2.

81. Frost HM. Vital biomechanics: proposed general concepts for skeletal adaptations to mechanical usage. Calcif Tissue Int. 1988 Mar;42(3):145-56.

82. Rubin CT, Lanyon LE. Regulation of bone mass by mechanical strain magnitude. Calcif Tissue Int. 1985 Jul;37(4):411-7.

83. O’Connor JA, Lanyon LE, MacFie H. The influence of strain rate on adaptive bone remodelling. J Biomech. 1982;15(10):767-81.

84. Lanyon LE, Rubin CT. Static vs dynamic loads as an influence on bone remodelling. J Biomech. 1984;17(12):897-905.

85. Beverly MC, Rider TA, Evans MJ, Smith R. Local bone mineral response to brief exercise that stresses the skeleton. BMJ. 1989 Jul 22;299(6693):233-5.

86. Duppe H, Gardsell P, Johnell O, Nilsson BE, Ringsberg K. Bone mineral density, muscle strength and physical activity. A population-based study of 332 subjects aged 15-42 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997 Apr;68(2):97-103.

87. Lauritzen JB, Petersen MM, Lund B. Effect of external hip protectors on hip fractures. Lancet. 1993 Jan 2;34(8836):11-3.

88. Buckler JE, Dutton TL, MacLeod HL, Manuge MB, Nixon MD. Use of hip protectors on a dementia unit. Physiother Can. 1997;Fall:297-9.

89. Parkkari J, Heikkila J, Kannus IP. Acceptability and compliance with wearing energy-shunting hip protectors: a 6-month prospective follow-up in a Finnish nursing home. Age Ageing. 1998 Mar;27(2):225-9.

90. Villar MT, Hill P, Inskip H, Thompson P, Cooper C. Will elderly rest home residents wear hip protectors? Age Ageing. 1998 Mar;27(2):195-8.

91. van Schoor NM, Smit JH, Twisk JW, Bouter LM, Lips P. Prevention of hip fractures by external hip protectors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003 Apr 16;289(15):1957-62.

92. van Schoor NM, Bruyne MC de, Roer R van der, Lommerse E, Tulder MW van, Bouter LM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of hip protectors in frail institutionalized elderly. Osteoporos Int. 2004 Dec;15(12):964-9.

93. van Schoor NM, Asma G, Smit JH, Bouter LM, Lips P. The Amsterdam Hip Protector Study: compliance and determinants of compliance. Osteoporos Int. 2003 Jun;14(4):353-9.

94. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189-98.

95. Engedal K, Haugen P, Gilje K, Laake P. Efficacy of short mental tests in the detection of mental impairment in old age. Compr Gerontol A. 1988 Jun;2(2):87-93.

96. Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993 May 12;269(18):2386-91.

97. Lewis CB, Bottomley JM. Geriatrie en fysiotherapie praktijk. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum. 1999.

98. Lundon KM, Li AM, Bibershtein S. Interrater and intrarater reliability in the measurement of kyphosis in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Spine. 1998 Sep 15;23(18):1978-85.

99. Bohannon RW. Muscle strength testing with hand-held dynamometers. In: Amundsen LR (ed) Muscle strength testing Instrumented and non-instrumented systems New York: Churchill Livingstone. 1990;69-88.

100. van der Ploeg RJ, Oosterhuis HJ, Reuvekamp J. Measuring muscle strength. J Neurol. 1984;231(4):200-3.

101. Bohannon RW. Hand-held dynamometry: factors influencing reliability and validity. Clin Rehabil. 1997 Aug;11(3):263-4.

102. Csuka M, McCarty DJ. Simple method for measurement of lower extremity muscle strength. Am J Med. 1985 Jan;78(1):77-81.

103. Reed R, Pearlmutter L, Yochum K, Meredith K, Mooradian A. The relationship between muscle mass and musscle strength in the elderly. JAGS. 1991;39:555-61.

104. Gajdosik RL, Bohannon RW. Clinical measurement of range of motion. Review of goniometry emphasizing reliability and validity. Phys Ther. 1987 Dec;67(12):1867-72.

105. Youdas JW, Bogard CL, Suman VJ. Reliability of goniometric measurements and visual estimates of ankle joint active range of motion obtained in a clinical setting. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993 Oct;74(10):1113-8.

106. Koch M, Gottschalk M, Baker DI, Palumbo S, Tinetti ME. An impairment and disability assessment and treatment protocol for community-living elderly persons. Phys Ther. 1994 Apr;74(4):286-94.

107. Lips P, Cooper C, Agnusdei D, Caulin F, Egger P, Johnell O, et al. Quality of life as outcome in the treatment of osteoporosis: the development of a questionnaire for quality of life by the European Foundation for Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 1997;7(1):36-8.

108. Lips P, Cooper C, Agnusdei D, Caulin F, Egger P, Johnell O, et al. Quality of life in patients with vertebral fractures: validation of the Quality of Life Questionnaire of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis (QUALEFFO). Working Party for Quality of Life of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 1999;10(2):150-60.

109. Garrett H, Vethenen S, Hill RA, Ebden P, Britton JR, Tattersfield AE. A comparison of six and twelve minute walk distance with 100 meter walk times in subjects with chronic bronchitis. Thorax. 1986;(41):425.

110. Butland RJ, Pang J, Gross ER, Woodcock AA, Geddes DM. Two-, six-, and 12-minute walking tests in respiratory disease. Br Med J. 1982 May 29;284(6329):1607-8.

111. Vos JA, Brinkhorst RA. Fietsergometrie bij begeleiding van training. Lochem-Gent: De Tijdstroom; 1987.

112. Lemmink K. De Groninger fitheidstest voor ouderen. Ontwikkeling van een meetinstrument. Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen; 1996.

113. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Lamb SE, Gates S, Cumming RG, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD007146.

115. Carter ND, Khan KM, Petit MA, Heinonen A, Waterman C, Donaldson MG, et al. Results of a 10 week community based strength and balance training programme to reduce fall risk factors: a randomised controlled trial in 65-75 year old women with osteoporosis. Br J Sports Med. 2001 Oct;35(5):348-51.

116. Carter ND, Khan KM, McKay HA, Petit MA, Waterman C, Heinonen A, et al. Community-based exercise program reduces risk factors for falls in 65- to 75-year-old women with osteoporosis: randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2002 Oct 29;167(9):997-1004.

117. Wu J. Effects of isoflavone and exercise on BMD and fat mass in postmenopausal Japanese women: a 1-year randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Bone Mineral Res. 2006;21(5):780-9.

118. Wu J. Cooperative effects of isoflavones and exercise on bone and lipid metabolism in postmenopausal Japanese women: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Metabolism. 2006;55(4):423-33.

119. Stengel SV. Power training is more effective than strength training for maintaining bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99(1):181-8.

120. von Stengel S, Kemmler W, Kalender WA, Engelke K, Lauber D. Differential effects of strength versus power training on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: A 2-year longitudinal study. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(10):649-55.

121. Korpelainen R. Effect of impact exercise on bone mineral density in elderly women with low BMD: a population-based randomized controlled 30-month intervention. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(1):109-18.

122. Korpelainen R. Effect of exercise on extraskeletal risk factors for hip fractures in elderly women with low BMD: a population-based randomized controlled trial. J Bone Mineral Res. 2006;21(5):772-9.

123. Bogaerts A. Impact of whole-body vibration training versus fitness training on muscle strength and muscle mass in older men: a 1-year randomized controlled trial. J Geron A Bio Sci Med. 2007;62(6):630-5.

124. Bogaerts A. Effects of whole body vibration training on postural control in older individuals: a 1 year randomized controlled trial. Gait Posture. 2007;26(2):309-16.

125. Luukinen H. Prevention of disability by exercise among the elderly: a population-based, randomized, controlled trial. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2006;24(4):199-205.

126. Luukinen H. Pragmatic exercise-oriented prevention of falls among the elderly: A population-based, randomized, controlled trial. Prev Med. 2007;44(3):265-71.

127. Li F, Harmer P, Fisher KJ, McAuley E. Tai Chi: improving functional balance and predicting subsequent falls in older persons. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004 Dec;36(12):2046-52.

128. Li F. Tai Chi and fall reductions in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(2):187-94.

129. Liu-Ambrose TYL, Khan KM, Eng JJ, Lord SR, Lentle B. Both resistance and agility training reduce back pain and improve health-related quality of life in older women with low bone mass. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(11):1321-9.

130. Liu-Ambrose T, Khan KM, Eng JJ, Janssen PA, Lord SR, McKay HA. Resistance and agility training reduce fall risk in women aged 75 to 85 with low bone mass: a 6-month randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 May;52(5):657-65.

131. Liu-Ambrose TY, Khan KM, Eng JJ, Heinonen A, McKay HA. Both resistance and agility training increase cortical bone density in 75- to 85-year-old women with low bone mass: a 6-month randomized controlled trial. J Clin Densitom. 2004;7(4):390-8.

132. Liu-Ambrose TY, Khan KM, Eng JJ, Gillies GL, Lord SR, McKay HA. The beneficial effects of group-based exercises on fall risk profile and physical activity persist 1 year postintervention in older women with low bone mass: follow-up after withdrawal of exercise. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 Oct;53(10):1767-73.

133. Vainionpaa A. Effects of high-impact exercise on bone mineral density: a randomized controlled trial in premenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(2):191-7.

134. Vainionpaa A, Korpelainen R, Vihriala E, Rinta-Paavola A, Leppaluoto J, Jamsa T. Intensity of exercise is associated with bone density change in premenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(3):455-63.

135. Vainionpaa A, Korpelainen R, Sievanen H, Vihriala E, Leppaluoto J, Jamsa T. Effect of impact exercise and its intensity on bone geometry at weight-bearing tibia and femur. Bone. 2007 Mar;40(3):604-11.

136. Heikkinen R. Acceleration slope of exercise-induced impacts is a determinant of changes in bone density. J Biomech. 2007;40(13):2967-74.

137. Jamsa T. Effect of daily physical activity on proximal femur. Clin Biomech (Bistol Avon). 2006;21(1):1-7.

138. Bonaiuti D. Exercise for preventing and treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(3).

139. Howe TE. Exercise for improving balance in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17(4).

140. de Kam D, Smulders E, Weerdesteyn V, Smits-Engelsman BC. Exercise interventions to reduce fall-related fractures and their risk factors in individuals with low bone density: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Osteoporos Int. 2009 Dec;20(12):2111-25.

141. Bergstrom I, Landgren B, Brinck J, Freyschuss B. Physical training preserves bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with forearm fractures and low bone mineral density. Osteoporos Int. 2008 Feb;19(2):177-83.

142. Bravo G, Gauthier P, Roy PM, Payette H, Gaulin P, Harvey M, et al. Impact of a 12-month exercise program on the physical and psychological health of osteopenic women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996 Jul;44(7):756-62.

143. Hourigan SR, Nitz JC, Brauer SG, O’Neill S, Wong J, Richardson CA. Positive effects of exercise on falls and fracture risk in osteopenic women. Osteoporos Int. 2008 Jan 11.

144. Iwamoto J. Effect of whole-body vibration exercise on lumbar bone mineral density, bone turnover, and chronic back pain in post-menopausal osteoporotic women treated with alendronate. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17(1572):163.

145. Judge JO. Home-based resistance training improves femoral bone mineral density in women on hormone therapy. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(9):1096-108.

146. Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, Winegard K, Ferko N, Parkinson W, Cook RJ, et al. Efficacy of home-based exercise for improving quality of life among elderly women with symptomatic osteoporosis-related vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2003 Aug;14(8):677-82.

147. Smulders E, Weerdesteyn V, Groen BE, Duysens J, Eijsbouts A, Laan R, et al. The efficacy of a short multidisciplinary falss prevention program for elderly persons with osteoporosis and a fall history: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:1705-11.

148. Swanenburg J. Effects of exercise and nutrition on postural balance and risk of falling in elderly people with decreased bone mineral density: Randomized controlled trial pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(6):523-34.

149. Iwamoto J, Takeda T, Otani T, Yabe Y. Effect of increased physical activity on bone mineral density in postmenopausal osteoporotic women. Keio J Med. 1998 Sep;47(3):157-61.

150. Iwamoto J, Takeda T, Ichimura S. Effect of exercise training and detraining on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Orthop Sci. 2001;6(2):128-32.

151. Madureira MM. Balance training program is highly effective in improving functional status and reducing the risk of falls in elderly women with osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(4):419-25.

152. Devereux K. Effects of a water-based program on women 65 years and over: a randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother. 2005;51(2):102-8.

153. Liu-Ambrose T, Eng JJ, Khan KM, Carter ND, McKay HA. Older women with osteoporosis have increased postural sway and weaker quadriceps strength than counterparts with normal bone mass: overlooked determinants of fracture risk? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003 Sep;58(9):M862-M866.

154. Chien MY, Yang RS, Tsauo JY. Home-based trunk-strengthening exercise for osteoporotic and osteopenic postmenopausal women without fracture – A pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19(1):28-36.

155. Hongo M. Effect of low-intensity back exercise on quality of life and back extensor strength in patients with osteoporosis: A randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(10):1389-95.

156. Malmros B, Mortensen L, Jensen MB, Charles P. Positive effects of physiotherapy on chronic pain and performance in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8(3):215-21.

157. Mitchell SL, Grant S, Aitchison T. Physiological Effects of Exercise on Post-menopausal Osteoporotic Women. Physiotherapy. 1998;84(4):157-63.

158. Maciaszek J. Effect of Tai Chi on body balance: randomized controlled trial in men with osteopenia or osteoporosis. Am J Chin Med. 2007;35(1):1-9.

159. Pearlmutter LL, Bode BY, Wilkinson WE, Maricic MJ. Shoulder range of motion in patients with osteoporosis. Arthritis Care Res. 1995 Sep;8(3):194-8.

160. Asikainen TM, Kukkonen-Harjula K, Miilunpalo S. Exercise for health for early postmenopausal women: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Sports Med. 2004;34(11):753-78.

161. Baker MK. Multi-modal exercise programs for older adults. Age Ageing. 2007;36(4):375-81.

162. Sheth P. Osteoporosis and exercise: a review. Mt Sinai J Med. 1999 May;66(3):197-200.

163. Swezey RL. Exercise for osteoporosis – is walking enough? The case for site specificity and resistive exercise. Spine. 1996 Dec 1;21(23):2809-13.

164. Wayne PM. The effects of Tai Chi on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(5):673-80.

165. Zehnacker CH. Effect of weighted exercises on bone mineral density in post menopausal women a systematic review. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2007;30(2):79-88.

166. Berard A, Bravo G, Gauthier P. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of physical activity for the prevention of bone loss in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 1997;7(4):331-7.

167. Kelley GA. Exercise and regional bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a meta-analytic review of randomized trials. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1998 Jan;77(1):76-87.

168. Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Tran ZV. Exercise and lumbar spine bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002 Sep;57(9):M599-M604.

169. Kelley GA. Exercise and bone mineral density at the femoral neck in postmenopausal women: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials with individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(3):760-7.

170. Martyn-St-James M. High-intensity resistance training and postmenopausal bone loss: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(8):1225-40.

171. Palombaro KM. Effects of walking-only interventions on bone mineral density at various skeletal sites: a meta-analysis. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2005;28(3):102-7.

172. Wolff I, van Croonenborg JJ, Kemper HC, Kostense PJ, Twisk JW. The effect of exercise training programs on bone mass: a meta-analysis of published controlled trials in pre- and postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9(1):1-12.

173. Borer KT. Walking intensity for postmenopausal bone mineral preservation and accrual. Bone. 2007;41(4):713-21.

174. Bunout D. Effects of vitamin D supplementation and exercise training on physical performance in Chilean vitamin D deficient elderly subjects. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41(8):746-52.

175. Chan K, Qin L, Lau M, Woo J, Au S, Choy W, et al. A randomized, prospective study of the effects of Tai Chi Chun exercise on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004 May;85(5):717-22.

176. Cheng S, Sipila S, Taaffe DR, Puolakka J, Suominen H. Change in bone mass distribution induced by hormone replacement therapy and high-impact physical exercise in post-menopausal women. Bone. 2002 Jul;31(1):126-35.

177. Chilibeck PD, Davison KS, Whiting SJ, Suzuki Y, Janzen CL, Peloso P. The effect of strength training combined with bisphosphonate (etidronate) therapy on bone mineral, lean tissue, and fat mass in postmenopausal women. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002 Oct;80(10):941-50.

178. Chubak J. Effect of exercise on bone mineral density and lean mass in postmenopausal women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(7):1236-44.

179. Ebrahim S, Thompson PW, Baskaran V, Evans K. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of brisk walking in the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Age Ageing. 1997 Jul;26(4):253-60.

180. Englund U. A 1-year combined weight-bearing training program is beneficial for bone mineral density and neuromuscular function in older women. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(9):1117-23.

181. Evans EM. Effects of soy protein isolate and moderate exercise on bone turnover and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2007;14(3 PT1):481-8.

182. Going S, Lohman T, Houtkooper L, Metcalfe L, Flint-Wagner H, Blew R, et al. Effects of exercise on bone mineral density in calcium-replete postmenopausal women with and without hormone replacement therapy. Osteoporos Int. 2003 Aug;14(8):637-43.

183. Gusi N. Low-frequency vibratory exercise reduces the risk of bone fracture more than walking: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskel Disord. 2006;30.

184. Karinkanta S, Heinonen A, Sievänen H, Uusi/Rasi K, Pasanen M, Ojala K, et al. A multi-component exercise regimen to prevent functional decline and bone fragility in home-dwelling elderly women: Randomized, controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(4):453-61.

185. Maddalozzo GF. The effects of hormone replacement therapy and resistance training on spine bone mineral density in early postmenopausal women. Bone. 2007;40(5):1244-51.

186. Milliken LA, Going SB, Houtkooper LB, Flint-Wagner HG, Figueroa A, Metcalfe LL, et al. Effects of exercise training on bone remodeling, insulin-like growth factors, and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with and without hormone replacement therapy. Calcif Tissue Int. 2003 Apr;72(4):478-84.

187. Rhodes EC, Martin AD, Taunton JE, Donnelly M, Warren J, Elliot J. Effects of one year of resistance training on the relation between muscular strength and bone density in elderly women. Br J Sports Med. 2000 Feb;34(1):18-22.

188. Sinaki M, Itoi E, Wahner HW, Wollan P, Gelzcer R, Mullan BP, et al. Stronger back muscles reduce the incidence of vertebral fractures: a prospective 10 year follow-up of postmenopausal women. Bone. 2002 Jun;30(6):836-41.

189. Stewart KJ. Exercise effects on bone mineral density relationships to changes in fitness and fatness. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(5):453-60.

190. Uusi-Rasi K, Kannus P, Cheng S, Sievanen H, Pasanen M, Heinonen A, et al. Effect of alendronate and exercise on bone and physical performance of postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Bone. 2003 Jul;33(1):132-43.

191. Woo J. A randomised controlled trial of Tai Chi and resistance exercise on bone health, muscle strength and balance in community-living elderly people. Age Ageing. 2007;36(3):262-8.

192. Young CM, Weeks BK, Beck BR. Simple, novel physical activity maintains proximal femur bone mineral density, and improves muscle strength and balance in sedentary, postmenopausal Caucasian women. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(10):1379-87.

193. Lock CA. Lifestyle interventions to prevent osteoporotic fractures: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(1):20-8.

194. No authors listed. Fall prevention programmes in older people. Evidence-Based Healthcare & Public Health. 2005.

195. Zijlstra GA. Interventions to reduce fear of falling in community-living older people: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(4):603-15.

196. Province MA, Hadley EC, Hornbrook MC, Lipsitz LA, Miller JP, Mulrow CD, et al. The effects of exercise on falls in elderly patients. A preplanned meta-analysis of the FICSIT Trials. Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies of Intervention Techniques. JAMA. 1995 May 3;273(17):1341-7.

197. Beyer N. Old women with a recent fall history show improved muscle strength and function sustained for six months after finishing training. Age Clin Exp Res. 2007;19(4):300-9.

198. Faber MJ, Bosscher RJ, Paw MJC, Wieringen PC van. Effects of exercise programs on falls and mobility in frail and pre-frail older adults: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(8):885-96.

199. Freiberger E. Preventing falls in physically active community-dwelling older people: a comparison of two intervention techniques. Gerontology. 2007;53(5):298-305.

200. Lin M. A randomized, controlled trial of fall prevention programs and quality of life in older fallers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(4):499-506.

201. Lord SR. The effect of an individualized fall prevention program on fall risk and falls in older people: A randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1296-304.

202. Mahoney JE, Shea TA, Przybelski R, Jaros L, Gangnon R, Cech S, et al. Kenosha County Falls Prevention Study: a randomized, controlled trial of an intermediate-intensity, community-based multifactorial falls intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(4):489-98.

203. Means KM. Balance, mobility, and falls among community-dwelling elderly persons: effects of a rehabilitation exercise program. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(4):238-50.

204. Sakamoto K. Effects of unipedal standing balance exercise on the prevention of falls and hip fracture among clinically defined high-risk elderly individuals: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sci. 2006;11(5):467-72.

205. Voukelatos A. A randomized, controlled trial of tai chi for the prevention of falls: the Central Sydney tai chi trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(8):1185-91.

206. Weerdesteyn V. A five-week exercise program can reduce falls and improve obstacle avoidance in the elderly. Gerontology. 2006;52(3):131-41.

207. Arai T. The effects of short-term exercise intervention on falls self-efficacy and the relationship between changes in physical function and falls self-efficacy in Japanese older people: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;82(2):133-41.

208. Donat H. Comparison of the effectiveness of two programmes on older adults at risk of falling: unsupervised home exercise and supervised group exercise. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(3):273-83.

209. Sattin RW, Easley KA, Wolf SL, Chen Y, Kutner MH. Reduction in fear of falling through intense Tai Chi exercise training in older, transitionally frail adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7).

210. Zhang J. The effects of Tai Chi Chuan on physiological function and fear of falling in the less robust elderly: an intervention study for preventing falls. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2006;42(2):107-16.

211. Heemskerk MC, Kempenaar MC, Eijkeren FJM van, Oomen WJM, Bakker M, et al. Fysiotherapie voor valpreventie: oefenen van spierkracht en balans. Ned Tijdschri Fysiother. 2007;117(5)(166):175.

212. Asikainen TM, Suni JH, Pasanen ME, Oja P, Rinne MB, Miilunpalo SI, et al. Effect of brisk walking in 1 or 2 daily bouts and moderate resistance training on lower-extremity muscle strength, balance, and walking performance in women who recently went through menopause: a randomized, controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2006;86(7):912-23.

213. Baker MK. Efficacy and feasibility of a novel tri-modal robust exercise prescription in a retirement community: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(1):1-10.

214. Beneka A. Resistance training effects on muscular strength of elderly are related to intensity and gender. J Sci Med Sport. 2005;8(3):274-83.

215. Bottaro M. Effect of high versus low-velocity resistance training on muscular fitness and functional performance in older men. Eur J Apl Physiol. 2007;99(3):257-64.

216. de Bruin ED. Effect of additional functional exercises on balance in elderly people. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(2):112-21.

217. de Vreede PL, Samson MM, Meeteren NLU van, Duursma SA, Verhaar HJJ. Functional-task exercise versus resistance strength exercise to improve daily function in older women: A randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):2-10.

218. Fahlman M. Combination training and resistance training as effective interventions to improve functioning in elders. J Ageing Phys Act. 2007;15(2):195-205.

219. Francisco-Donoghue J. Comparison of once-weekly and twice-weekly strength training in older adults. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:19-22.

220. Galvao DA. Resistance exercise dosage in older adults: Single- versus multiset effects on physical performance and body composition. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2090-7.

221. Henwood TR. Short-term resistance training and the older adult: the effect of varied programmes for the enhancement of muscle strength and functional performance. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2006;26(5):305-13.

222. Kalapotharakos VI, Tokmakidis SP, Smilios I, Michalopoulos M, Gliatis J, Godolias G. Resistance training in older women: effect on vertical jump and functional performance. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2005;45(4):570-5.

223. Kalapotharakos VI. Functional and neuromotor performance in older adults: Effect of 12 wks of aerobic exercise. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(1):61-7.

224. Klentrou P. Effects of exercise training with weighted vests on bone turnover and isokinetic strength in postmenopausal women. J Ageing Phys Act. 2007;15(3):278-99.

225. Mangione KK. Can elderly patients who have had a hip fracture perform moderate- to high-intensity exercise at home? Phys Ther. 2005;85(8):727-39.

226. Manini T. Efficacy of resistance and task-specific exercise in older adults who modify tasks of everyday life. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(6):616-23.

227. Orr R. Power training improves balance in healthy older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(6):78-85.

228. Rosendahl E. High-intensity functional exercise program and protein-enriched energy supplement for older persons dependent in activities of daily living: a randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52(2):105-13.

229. Sullivan DH. Effects of muscle strength training and megestrol acetate on strength, muscle mass, and function in frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(1):20-8.

230. Symons TB, Vandervoort AA, Rice CL, Overend TJ, Marsh GD. Effects of maximal isometric and isokinetic resistance training on strength and functional mobility in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;66(6):777-81.

231. Topp R. Exercise and functional tasks among adults who are functionally limited. West J Nurs Res. 2005;27(3):252-70.

232. Tracy BL. Steadiness training with light loads in the knee extensors of elderly adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(4):735-45.

233. Tsourlou T. The effects of a twenty-four-week aquatic training program on muscular strength performance in healthy elderly women. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20(4):811-8.

234. Bruyere O. Controlled whole body vibration to decrease fall risk and improve health-related quality of life of nursing home residents. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(2):303-7.

235. Cheung WH. High-Frequency Whole-Body Vibration Improves Balancing Ability in Elderly Women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(7):852-7.

236. Marsh AP, Katula JA, Pacchia CF, Johnson LC, Koury KL, Rejeski WJ. Effect of treadmill and overground walking on function and attitudes in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(6):1157-64.

237. Sousa N. Effects of progressive strength training on the performance of the Functional Reach Test and the Timed Get-Up-and-Go Test in an elderly population from the rural north of Portugal. Am J Hum Biol. 2005;17(6):746-51.

238. Yang Y. Effect of combined Taiji and Qigong training on balance mechanisms: a randomized controlled trial of older adults. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13(8):CR339-CR348.

239. Audette JF, Jin YS, Newcomer R, Stein L, Duncan G, Frontera WR. Tai Chi versus brisk walking in elderly women. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):388-93.

240. Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Tran ZV. Exercise and bone mineral density in men: a meta-analysis. J Appl Physiol. 2000 May;88(5):1730-6.

241. Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Tran ZV. Resistance training and bone mineral density in women: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001 Jan;80(1):65-77.

242. Kelley GA, Kelley KS. Efficacy of resistance exercise on lumbar spine and femoral neck bone mineral density in premenopausal women: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2004 Apr;13(3):293-300.

243. Ernst E. Exercise for female osteoporosis. A systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Sports Med. 1998 Jun;25(6):359-68.

244. Huuskonen J, Vaisanen SB, Kroger H, Jurvelin JS, Alhava E, Rauramaa R. Regular physical exercise and bone mineral density: a four-year controlled randomized trial in middle-aged men. The DNASCO study. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12(5):349-55.

245. Kontulainen S, Heinonen A, Kannus P, Pasanen M, Sievanen H, Vuori I. Former exercisers of an 18-month intervention display residual aBMD benefits compared with control women 3.5 years post-intervention: a follow-up of a randomized controlled high-impact trial. Osteoporos Int. 2004 Mar;15(3):248-51.

246. Shirazi KK. A home-based, transtheoretical change model designed strength training intervention to increase exercise to prevent osteoporosis in Iranian women aged 40-65 years: a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(3):305-17.

247. Kemper HCG. Mijn Beweegreden. Maarssen: Elsevier Gezondheidszorg; 2004.

248. Kemper HCG, Ooijendijk WTM. De Nederlandse Norm voor Gezond Bewegen, een update met bezinning over cummunicatie. In: Hildebrandt VH, Ooijendijk WTM, Stiggelbout M, Hopman-Rock M, Trendraport Bewegen en Gezondheid. TNO Kwaliteit van Leven, Hoofddorp/Leiden: 2004.

249. Verhaar HJJ, et al. CBO-Richtlijn preventie van valincidenten bij ouderen. Utrecht: Kwaliteitsinstituut voor de gezondheidszorg CBO; 2004.

250. Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, Duncan PW, Judge JO, King AC, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007 Aug 28;116(9):1094-105.

251. de Vries H, Mudde AN, Dijkstra A. The attitude-social influence-efficacy model applied to the prediction of motivational transitions in the process in smoking cessation. In: Norman P, Abraham C, Conner M, editors, Understanding and changing health behaviour: From Health Beliefs to Self-regulation Amsterdam: Harwood Academic. 2000;165-87.

252. van Burken P, Swank J. Gezondheidspsychologie voor de fysiotherapeut. Houten/Diegem: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum; 2000.

253. Kulp JL, Rane S, Bachmann G. Impact of preventive osteoporosis education on patient behavior: immediate and 3-month follow-up. Menopause. 2004 Jan;11(1):116-9.

254. Shin YH, Hur HK, Pender NJ, Jang HJ, Kim MS. Exercise self-efficacy, exercise benefits and barriers, and commitment to a plan for exercise among Korean women with osteoporosis and osteoarthritis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006 Jan;43(1):3-10.

255. Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, McKeever CD, Hangartner T, Keller M, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy With Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. JAMA. 1999 Oct 13;282(14):1344-52.

256. Pols HA, Felsenberg D, Hanley DA, Stepan J, Munoz-Torres M, Wilkin TJ, et al. Multinational, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of the effects of alendronate on bone density and fracture risk in postmenopausal women with low bone mass: results of the FOSIT study. Fosamax International Trial Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9(5):461-8.

257. Stel VS, Smit JH, Pluijm SM, Visser M, Deeg DJ, Lips P. Comparison of the LASA Physical Activity Questionnaire with a 7-day diary and pedometer. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004 Mar;57(3):252-8.

258. Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991 Feb;39(2):142-8.

259. Duncan PW, Studenski S, Chandler J, Prescott B. Functional reach: predictive validity in a sample of elderly male veterans. J Gerontol. 1992 May;47(3):M93-8.

260. Edelaar MJA, Geffen J van, Wijnker J. Het One Repetion Maximum en submaximale testen. Sportgericht. 2005;59(2):33-7.

261. van de Goolberg T. Het Kracht Revalidatie Systeem (KRS). Richting Sportgericht. 2004;58(5/6):46-52.

262. Takken T. De 6-Minutenwandeltest: bruikbaar meetinstrument. Stimulus. 2005;24:244-58.

B.4 (Aanvullend) onderzoek

Het onderzoek bestaat uit: inspectie/observatie, palpatie, lichamelijk onderzoek en vaardigheidsanalyse. De omvang van en de strategie voor het onderzoek zijn afhankelijk van de hulpvraag en het (de) probleemgebied(en) van de patiënt. Doel is het inventariseren van actuele stoornissen en beperkingen in relatie tot de participatieproblemen.

Prognostische factoren voor een verhoogd valrisico

- Niet zonder handen uit de stoel kunnen opstaan.

- Verminderd evenwicht tijdens draaien (360º).

- Verminderd evenwicht bij het staan op één been en omhoog reiken.

- Stoppen met lopen tijdens praten.

- Lagere staphoogte (voet niet helemaal van de grond)

- Kortere staplengte (voet niet voorbij andere voet)

- Minder stapcontinuïteit (stoppen tussen passen)

- Moeite met draaien tijdens het lopen (niet vloeiend).

Deze factoren worden getest met de Get-Up-and-Go test (GUG). In zijn algemeenheid geldt dat er sprake is van een verhoogd valrisico als de GUG langer duurt dan 20 seconden.

B.4.1 Inspectie/observatie en palpatie

- Zijn er tekenen van wervelimpressie?

Kenmerkend voor een wervelimpressie is een afgenomen lichaamslengte en/of een thoracale kyfose. Ook kloppijn van de midthoracale wervels is indicatief voor wervelimpressie; deze kloppijn kan echter een symptoom zijn van een tumor of ontstekingsproces. - Observatie van de houding, indien mogelijk in de thuissituatie van de patiënt, in zit (aan tafel, tv-kijkend en in bed) en in stand, om te kunnen vaststellen of de houding aanleiding kan geven tot klachten.

- Observatie van gang en balans tijdens bewegingen in adl-gerelateerde situaties om een indruk te krijgen van het valrisico. adl-gerelateerde bewegingen zijn eenvoudig uit te voeren tijdens het diagnostisch of therapeutisch proces. Als er bij een van deze bewegingen sprake is van prognostische kenmerken van een verhoogd valrisico, moeten gang en/of balans uitgebreid worden onderzocht.

Kenmerken van wervelimpressie zijn: toename van de thoracale kyfose, abdominale protrusie, kort bovenlijf, toename van de cervicale lordose, de onderste ribben raken de bekkenkam, vermindering van lengte (> 40 jaar is 1,5 cm per 10 jaar normaal, > 3 cm is abnormaal), verschil tussen de spanwijdte minus de lichaamslengte > 5 cm.

Kloppijn, maar ook (as)drukpijn worden beschouwd als indicatief voor wervelpathologie, maar het ontbreken van deze symptomen betekent niet dat er geen wervelpathologie kan zijn (Hirchberg et al. in de ‘NHG-Standaard Osteoporose’1).

B.4.2 Lichamelijk onderzoek

De fysiotherapeut onderzoekt de spier- en gewrichtsfunctie van de wervelkolom en functies/activiteiten die zijn gerelateerd aan het valrisico. Het lichamelijk onderzoek omvat:

- meten van de spierfunctie: kracht en uithoudingsvermogen van extensoren wervelkolom;

- meten van de gewrichtsfunctie: extensie wervelkolom;

- inventariseren van de factoren die zijn gerelateerd aan het valrisico:

- spierfunctie: kracht en uithoudingsvermogen van de spieren van de onderste extremiteit (met name de m. tibialis anterior);

- gewrichtsfunctie: mobiliteit van de gewrichten van de onderste en bovenste extremiteiten;

- bewegingspatronen: gang en balans;

- transfers.

Bij het lichamelijk onderzoek kunnen meetinstrumenten worden gebruikt. Zie paragraaf B.5.

B.4.3 Aanvullend onderzoek

Bij een vermoeden van een verhoogd valrisico als gevolg van een verminderde spierkracht of balans kunnen in het aanvullend onderzoek verschillende meetinstrumenten worden afgenomen.

In aanvulling op de aanbevolen meetinstrumenten, die in paragraaf B.5 worden benoemd, kan de fysiotherapeut, indien gewenst, de volgende aanvullende onderzoeken verrichten (optionele meetinstrumenten):

- Situatieanalyse, bestaande uit omgevings- en schoeiselcontrole. Patiënten kunnen de veiligheid in en om hun huis zelf controleren met behulp van de checklist ‘Veiligheid en valpreventie in en om het huis’ van de Osteoporose Stichting.

- Kwaliteit van leven. De Qualitiy of life vragenlijst QUALEFFO kan worden gebruikt om bevindingen te objectiveren en het handelen te evalueren.

- Relatie belasting-belastbaarheid. De fysiotherapeut test de conditie met behulp van de 6-Minuten wandeltest, de Astrand-fietstest (AF) of een wandeltest met oplopende snelheid.

B.5 Meetinstrumenten

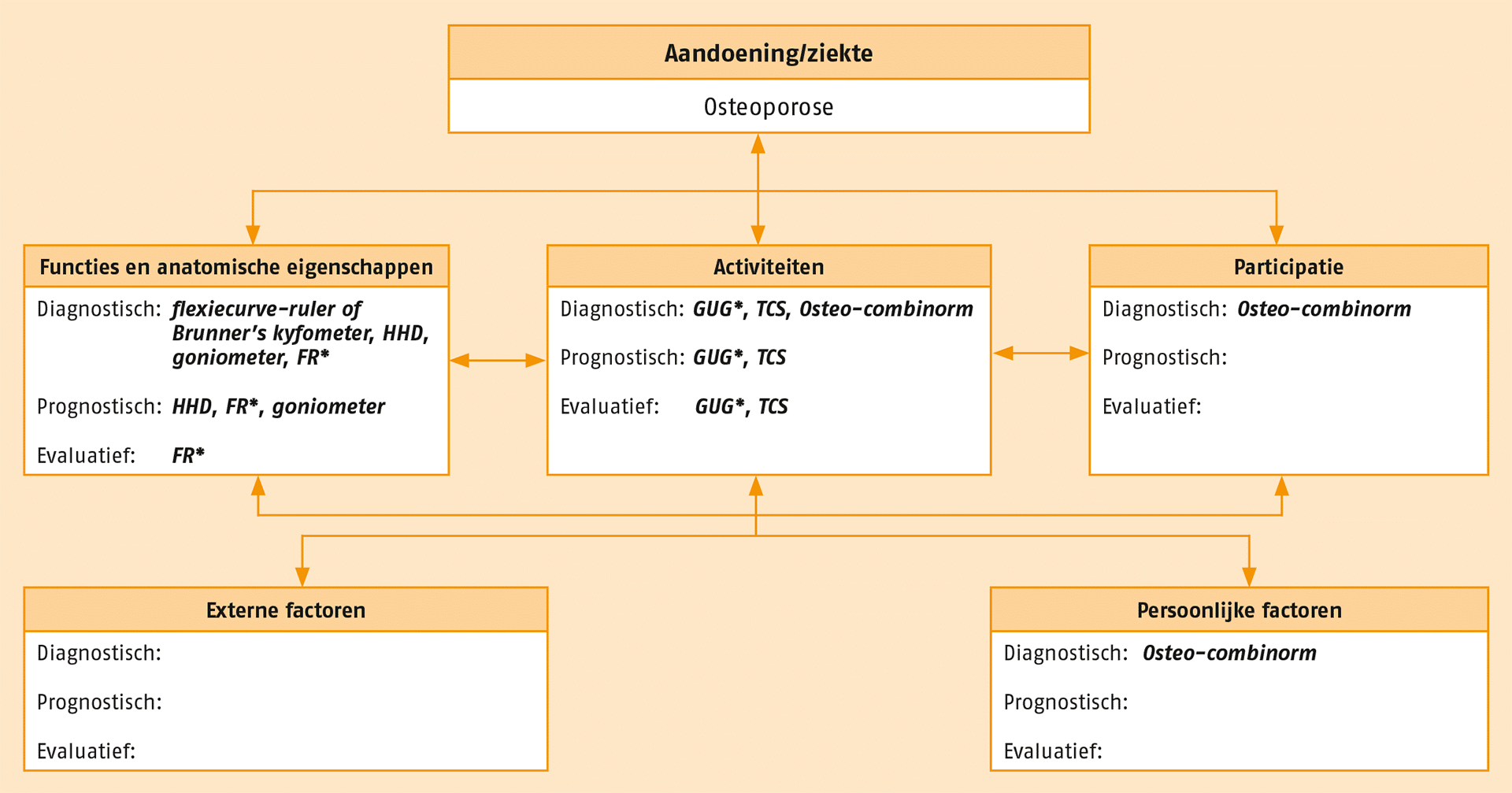

De meetinstrumenten die van toepassing kunnen zijn bij patiënten met osteoporose zijn op systematische wijze gekoppeld aan de gezondheidsdomeinen van de ICF. In de volgende figuur staat een overzicht van de aanbevolen meetinstrumenten. Deze instrumenten kunnen worden toegepast wanneer daar in de praktijk aanleiding toe is. De optionele meetinstrumenten staan in de Verantwoording en toelichting. Al deze meetinstrumenten zijn beschikbaar via www.meetinstrumentenzorg.nl.

Overzicht van de aanbevolen meetinstrumenten.

FR = Functional Reach; Flexiecurver ruler of Brunners’s kyfometer; Goniometer; GUG = Get-Up-and-Go test; HHD = Hand-Held Dynamometer; Osteo-combinorm; TCS = Timed Chair Stand test.

Cursief = performancetest/functietest; niet cursief = vragenlijst/observatielijst.

* Voor het bepalen van valrisico.

NB Voor het in kaart brengen van activiteiten, participatie, externe en persoonlijke factoren zijn in deze richtlijn geen aanbevolen meetinstrumenten beschreven.

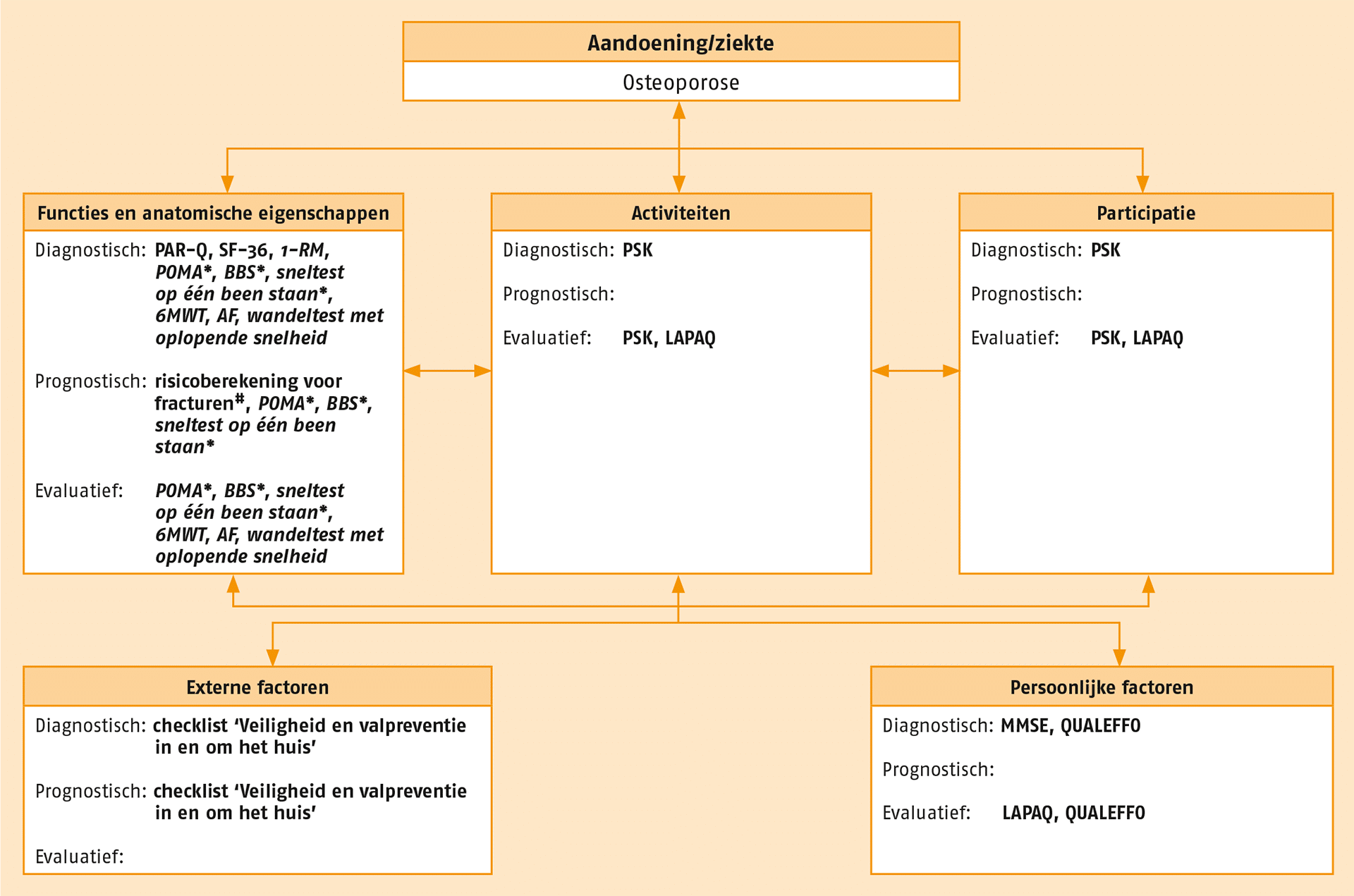

De volgende tabel geeft voor een aantal relevante parameters aan welke aanbevolen meetinstrumenten beschikbaar zijn om de parameters te objectiveren.

Aanbevolen meetinstrumenten om relevante parameters bij patiënten met osteoporose te objectiveren.

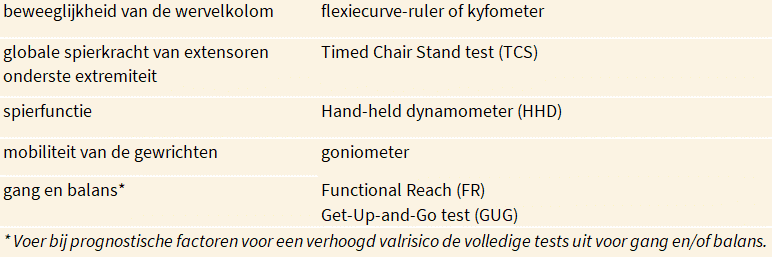

In de volgende figuur staan de optionele meetinstrumenten. Instrumenten uit beide sets kunnen worden toegepast wanneer daar in de praktijk aanleiding toe is. Al deze meetinstrumenten zijn beschikbaar via www.meetinstrumentenzorg.nl.

Overzicht van de aanbevolen meetinstrumenten.

1RM = one-repetition maximum schattingstest; 6MWT = Zes-minuten wandeltest; AF = Astrand submaximale Fietstest; BBS = Berg Balance Scale; LAPAQ = LASA Physical Activity Questionnaire; MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination; PAR-Q = Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire; POMA = Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment; PSK = Patiënt Specifieke Klachten; QUALEFFO = Quality of Life for Osteoporosis; SF-36.

Cursief = performancetest/functietest; niet cursief = vragenlijst/observatielijst

* Voor het bepalen van valrisico. # De risicoberekening voor fracturen kan gedaan worden met de FRAX Calculation Tool of met de Garvan Fracture Risk Calculator of met de checklist ‘Risicofactoren voor vallen en fracturen’

Bron: Raamwerk Klinimetrie voor evidence based products. Swinkels RAHM, Meerhoff GA, Beekman E, Beurskens AJHM. Amersfoort: KNGF; 2016.

Gewrichtsfunctie (wervelkolom)

De flexiecurve-ruler en Brunner’s kyfometer zijn betrouwbare instrumenten om de kyfose te meten. De kyfometer heeft de grootste betrouwbaarheid, maar met de flexiecurve-ruler kan de houding ook kwantitatief worden beoordeeld.98 De kyfose kan ook worden gemeten door de patiënt met de rug tegen de muur laten staan, en de afstand te bepalen tussen de wervel C7 en de muur. Dit geeft een indruk van de ernst van de kyfose. Verscheidene metingen maken eventuele vooruitgang zichtbaar.

Spierfunctie

Een Hand-held dynamometer is een betrouwbaar instrument om de spierkracht te meten. Het instrument is in de praktijk goed toepasbaar; het is relatief goedkoop, draagbaar en nauwkeurig.99,100 Om de betrouwbaarheid te vergroten, moet de meting zo veel mogelijk worden gestandaardiseerd aan de hand van een meetprotocol; het resultaat is onder andere afhankelijk van de positie van de dynamometer.101 In het protocol worden ook vastgelegd: de houding van de patiënt, de testtechniek en -procedure, de naam van de fysiotherapeut die de test afneemt, de instructie die de patiënt krijgt en het type dynamometer. Met behulp van de 1-RM schattingstest kan de (maximale) spierkracht worden geschat zonder dat een patiënt een 1 RepMax hoeft uit te voeren (1 RepMax is 1 herhalingsmaximum: het gewicht dat de patiënt maximaal 1 keer kan optillen). Een eenvoudige test voor de globale spierkracht van de extensoren van de benen is de Timed Chair Stand test.102 De indicatiewaarden staan in de volgende tabel.

Indicatiewaarden voor de Timed Chair Stand test (TCS)102 en spierkracht bij ouderen.103

| Timed stands test (in sec) | dorsaalflexie enkel (kg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| leeftijd | vrouw | man | leeftijd | vrouw li-re | man li-re |

| 50 | 20,9 | 18,1 | 55-64 | 22,3-22,0 | 29,4-30,2 |

| 60 | 22,6 | 20,1 | 65-74 | 20,8-21,5 | 27,9-28,1 |

| 70 | 24,3 | 22,0 | |||

| 80 | 26,1 | 24,0 | 75+ | 17,8-18,5 | 25,9-26,5 |

| flexie knie (kg) | extensie knie (kg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| leeftijd | vrouw | man | leeftijd | vrouw li-re | man li-re |

| 55-64 | 17,7-18,0 | 25,8-26,2 | 55-64 | 24,0-23,9 | 30,4-30,0 |

| 65-74 | 13,8-13,8 | 20,22,2-22,0 | 65-74 | 21,4-21,3 | 28,4-27,8 |

| 75+ | 12,3-12,6 | 18,8-18,7 | 75+ | 19,5-19,7 | 25,4-25,5 |

Indicatie voor behandeling

Een spierkracht 70% van de verachte spierkracht is indicatie voor behandeling.

Gewrichtsfunctie (bovenste en onderste extremiteiten)

De goniometer kan worden gebruikt om de mobiliteit van gewrichten te meten. Het meetinstrument is makkelijk toepasbaar en goedkoop. De goniometer heeft een goede betrouwbaarheid, mits een gestandaardiseerde procedure wordt gehanteerd.104,105

Indicatie voor behandeling

Behandeling is geïndiceerd wanneer de mobiliteit minder is dan nodig is voor adl (zie de volgende tabel).106

Mobiliteit van gewrichten die nodig is voor het uitvoeren van adl.

| schouder | elleboog | heup | knie | enkel |

| flexie: 150° | flexie: 140° | flexie: 90° | flexie: 90° | plantaire flexie: neutraal |

| extensie: 20° | extensie: 20° | extensie: 10° | extensie: 10° | dorsale flexie: neutraal |

| abductie: 90° |

Evenwicht / balansanalyse / transfers

De Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment (POMA) (onderdeel evenwicht), de Berg Balance Scale (BBS), de Functional Reach (FR) en de Get-Up-and-Go test (GUG) zijn betrouwbare en valide meetinstrumenten om evenwicht en balans in kaart te brengen.

De POMA en de BBS zijn beide bedoeld om balans te meten. De POMA heeft 2 antwoordcategorieën en is hiermee grover en minder gevoelig dan de BBS, die 4 antwoordcategorieën heeft. Voordeel van de POMA is dat er ook een onderdeel voor ganganalyse is. De FR en de GUG zijn eenvoudig en snel toepasbaar en zijn te gebruiken als screeningsinstrument, evenals de sneltest waarbij de patiënt zo lang mogelijk op 1 been gaat staan.

Indicatie voor behandeling

Indien een patiënt bij de transfers meerdere pogingen nodig heeft, overmatig in een bepaalde richting leunt, zijn balans tijdens dagelijkse functionele activiteiten niet kan houden, in een bepaalde richting balans verliest, zich moet vasthouden aan iets of iemand om zijn balans niet te verliezen of als er onveilige momenten zijn tijdens de transfer (bijvoorbeeld te veel op het puntje van de stoel zitten).106

Ganganalyse

De POMA heeft een onderdeel voor het doen van een ganganalyse.

Indicatie voor behandeling

Indien een patiënt struikelt of correctiestappen moet maken, bij verlies van balans door te veel naar voren, naar opzij of naar achteren te leunen, bij verlies van balans tijdens het draaien en indien de patiënt tijdens het lopen naar objecten reikt om steun te zoeken, bij afgenomen staplengte die resulteert in consistent minder op het ene been staan dan op het andere, bij afgenomen staphoogte, bij niet goed afwikkelen en afwijken van de looprichting die resulteert in zwaaibewegingen van de romp, is er een indicatie voor behandeling. Dit kan duidelijker worden bij sneller wandelen.106

Aanvullende onderzoeken

Kwaliteit van leven (Quality of Life for Osteoporosis (QUALEFFO))

Deze vragenlijst is ontwikkeld door een werkgroep van de Europese Stichting voor Osteoporose.107 De doelgroep omvat patiënten met wervelfracturen als gevolg van osteoporose. De betrouwbaarheid van de lijst bij patiënten met osteoporose en minimaal 1 wervelfractuur is goed en patiënten met een wervelfractuur hebben een lagere score op de vragenlijst dan gezonde mensen van dezelfde leeftijd en hetzelfde geslacht.108